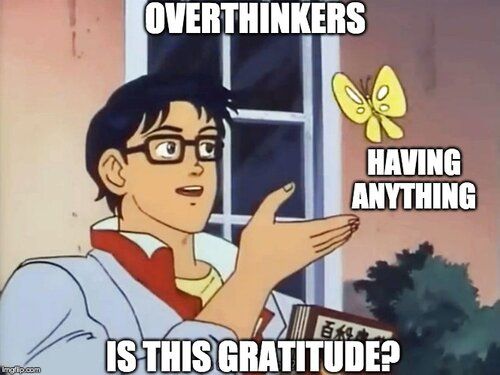

Does “Gratitude” Make Sense?

A skeptic’s guide to gratitude.

Gratitude is hard for me.

While I'm not not thankful for what I have, I can't shake the sense that "gratitude" just isn't the correct characterization of what's going on here.

Gratitude's prominent place in the positive psychology-type canon is ~evidence based~. When they make people do "gratitude journals" or whatever, the people report becoming happier. Well, fine and good. Gratitude journaling isn't going to make you a worse person.

Still, gratitude practices seem like a trick to me. Humans are just hyper-status-conscious primates. When we are invited to compare ourselves to our salient peers, we feel miserable to find we're lower down the totem pole than we'd like to be. (This is why rich people in poor neighborhoods are happier than actually-richer people in even-richer neighborhoods).

Gratitude encourages us always to compare down no matter what, to actual other people (or our hypothetical alternative selves) who have less. This unidirectional comparison may have the immediate effect of boosting happiness. But why is it otherwise justified?

I want to know which social comparisons are actually the right ones to make, all things considered (and some of my clients want to know this, too). The right social comparisons might be the ones that expediently lead to happiness, in terms of subjective momentary positive affect. Or not.

Maybe gratitude constitutes some kind of exception to the ordinary pursuit of happiness which (spoiler alert) is complicated if not largely just doomed.

Happiness is best approached indirectly, as a side effect of doing independently-worthwhile things, pursued for their own sake.

But once you learn this, the side-effect theory of happiness, you can't quite forget it in the way the theory requires. Oops!

Here's where gratitude might help: perhaps gratitude, as an emotion, is more musterable than happiness per se (though gratitude does then point in that general direction). In that case, gratitude journaling is not charitably interpreted as a cognitive exercise of dubious suppositions. Instead, it aims more at producing a mood. Fair enough.

One other thing, though - in ordinary language, we don't usually say "thanks" into the ether. Giving thanks to God makes plenty of sense. Otherwise, to whom are we speaking?

Well, it's complicated. I am thankful to my husband, for innumerable goods. I am thankful to my children - though they don't really bear responsibility for the value they've brought to my life so far, with any luck they will become aware of this and responsible for it later. I am thankful to my parents, for all their faults (and one's dead). I am thankful for a sociopolitical climate that, for all its faults, still respects many critical liberties.

Luck plays a large role always and everywhere. But making the best of lucky situations involves taking responsibility in an art learned over time. So, to that extent, I am thankful for the proto-wisdom embedded here and there within my wayward collection of past selves. The passivity of luck can indeed be rendered active. I do my best to honor these lucks-well-received moving forward.

All of the foregoing doesn't make for a straightforward happiness-oriented journaling practice, and it's not something I can explain to my very young children. But that's what "gratitude" means to me.

Gratitude is a feeling not a judgement, an orientation not a lifehack. What's good about gratitude helps us to get out of our monkey minds, not to burrow further into them.

Gratitude seems to mean you'd find something else to be thankful for even if you lost the things you name today. If only for aesthetic reasons, the endlessly deep capacity for humans to make meaning must be taken as a feature and not a bug.

Pamela J. Hobart - Philosophical Life Coaching Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.